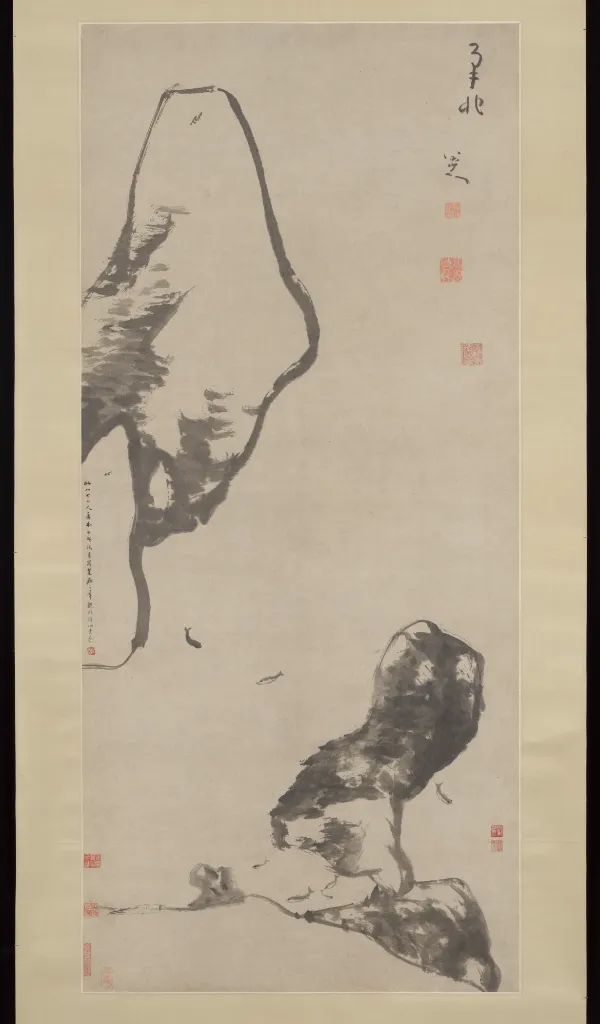

Fish and Rocks

by Bada Shanren

Description

Fish and Rocks (late seventeenth century) is a striking ink-on-paper work by one of the most enigmatic masters of early Qing painting, Bada Shanren (Zhu Da), a descendant of the Ming imperial house who became a leading figure of the so‑called “Individualist” tradition. What appears at first to be a simple garden pond framed by two ornamental rocks is transformed by Bada’s minimalist, calligraphic handling into something profoundly disquieting. Two massive, ink-dark rock forms loom over a nearly blank expanse that only resolves into water once the viewer notices seven tiny fish gliding beneath them. Six are shown in clear profile, while one is rendered from an unexpected overhead view—an abrupt shift in perspective that unsettles the eye. With no horizon line and broad areas of empty space, the composition seems to hover between abstraction and representation, between natural scene and psychological projection.

Artistic and Social Context Zhu Da was born into the Ming imperial lineage and, after the Manchu conquest of 1644, later accounts relate that he took refuge in a Buddhist temple, living as a monk and effectively withdrawing from public life. By around 1680 he appears to have left monastic life and begun supporting himself through painting and calligraphy, and by 1684 he was using the alternative name Bada Shanren (“Mountain Man of the Eight Greats”). Long regarded as a steadfast Ming loyalist, he has often been seen as using painting and calligraphy as subtle yet potent means of expressing the concerns of the yimin, or “leftover subjects” who survived the dynasty they had served. Fish and Rocks, created in the last two decades of his life, belongs to the mature period when Bada had perfected a distilled, symbolic visual language that blends emotional intensity with cryptic, often ambivalent imagery.

Interpretation and Meaning In Fish and Rocks, the seemingly decorative motif of rocks and fish becomes, in Bada’s treatment, a charged psychological field. The disproportion between monumental rocks and minuscule fish, the oscillation between solid and void, and the deliberate confusion of spatial cues create a sense of unease that many viewers feel extends far beyond the literal scene. The lone fish viewed from above—breaking the coherence of perspective—acts almost as a visual jolt, suggesting displacement, disorientation, or a world out of alignment. Commentators have often read this tension as an encoded reflection of Bada’s own situation: a displaced nobleman, a hidden loyalist, and a witness to a lost world. Within this interpretive framework, the painting’s stark contrasts and enigmatic structure become metaphors for survival, suppressed identity, and the instability of existence under foreign rule, even though other, less politically focused readings remain possible. In this way, Bada transforms a humble pond into a moral and emotional landscape, its quiet surface seeming to conceal profound inner turbulence.

Size and Location The painting’s image area measures approximately 53 × 23 7/8 inches (about 134.6 × 60.6 cm). It is preserved in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.